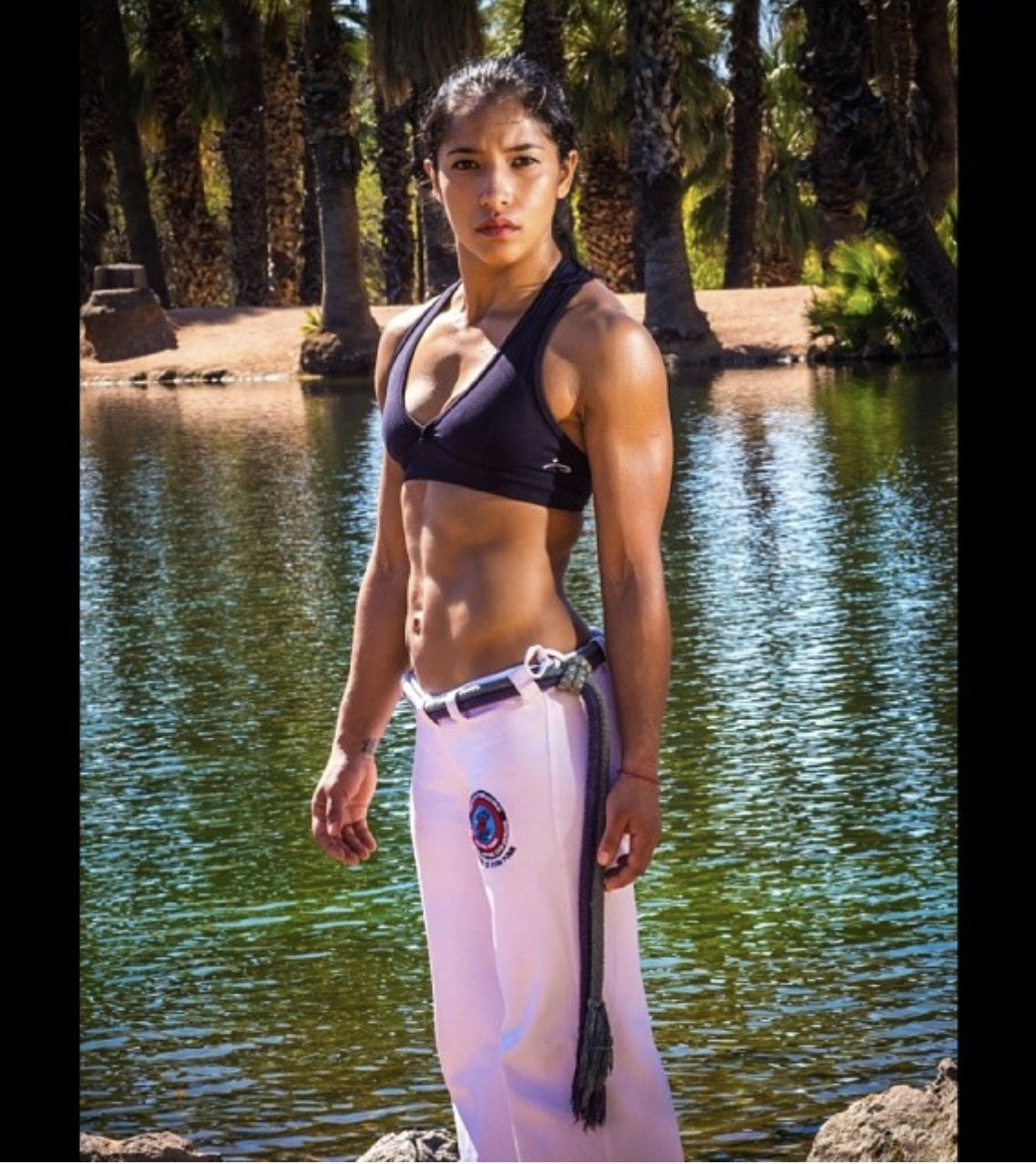

Episode 728 - Professora Morena Lima

Professora Morena Lima is a martial arts practitioner and instructor of BJJ and Capoeira. She’s a physiotrainer and she uses her own Rooted Strength Method.

I’m always trying to have a different view of the world and be reminded that my goal in life is to grow, evolve, and get better. I don’t even want to be that same person I was last week…

Professora Morena Lima - Episode 728

Growing up in an environment where violence was a norm, it won’t take that long for you to become violent as well. However, for Professora Morena Lima, her childhood made her abhor violence. Upon learning martial arts for self-defense and overcoming bullying, violence became normal upon migrating to the United States. Professora eventually found Capoeira and it was a breath of fresh air.

Presently, Professora Morena Lima is a Physiotrainer working with healing and preventing injury for martial artists. She teaches her own method called Rooted Strength Method, which incorporates physio training principles, breath work, mindfulness, and unconventional weight lifting (steel mace, kettlebells, bands, and body weight). Professora Lima’s method is helping martial artists to be more mindful and to love themselves enough to have a proper recovery to build more resilient bodies. Using micro habits to rewire the brain and wake up from automatic using breath and mindfulness tools to get there.

In this episode, Professora Morena Lima talks about her experience with violence, overcoming bullying, and her work as a Physiotrainer. Listen to learn more!

Show Notes

For more information, check out Professora Morena Lima’s Rooted Strength Method

Show Transcript

You can read the transcript below.

Jeremy Lesniak: Welcome! This is whistlekick Martial Arts Radio, episode 728 with today's guest, Professora Morena Lima.

I'm Jeremy Lesniak. I'm your host for the show. I founded whistlekick because I wanted to support traditional martial arts and traditional martial artists, probably people like you. If you want to know more about what we are doing to support the industry and the people, go to whistlekick.com. It's our online home. It's the place to find all the things that we're working on, because it's a long list. It's also the place you’ll find our store, because yeah, working on this stuff requires some money, and those of you that pick stuff up, it helps us move forward. Head on over there, grab yourself a shirt, or a hat, or protective gear, or any of the other cool stuff that we've got going.

The show, Martial Arts Radio, gets its own website, and you can probably guess what it is. If you're new, whistlekickmartialartsradio.com. We keep it easy. You'll see new episodes of the show twice a week. We never hide any of the old episodes behind a paywall because the entire purpose of what we do, the goal of the show and whistlekick overall, it's all under the heading of connecting, educating, and entertaining traditional martial artists worldwide.

If you want to support the work that we do, there are lots of ways you can help out. You can make a purchase, you could share an episode, or join our Patreon, patreon.com/whistlekick. It's the place to go for that. You can support us monthly with as little as $2. If you spend $5, you get bonus audio, $10 gets you video content, and it goes up from there. Everything but that $2 tier, you get bonus merch that we send out, just … We’ll throw that your way, too. We work really hard to make sure that the people who contribute to the Patreon get more than they ever imagined.

If you want the whole list of all the things that you can do to help us out from the free to the paid, type in whistlekick.com/family. We put that hurdle in front of you because we want to make sure that it's only the people who really love what we do that get the benefits of that page.

Today's episode, as I'm sure you could guess, involves stories, stories of not only coming to America, but discovering where one fits in, in a country, fits in with other people, fits in within the martial arts. I don't think I can say anything more without giving things away, so I'm not going to do that. I loved this episode, and I loved how things unfolded. I hope you do, too.

Morena, welcome to whistlekick Martial Arts Radio.

Morena Lima: Thank you so much. It is a pleasure to be here.

JL: It's a pleasure to have you here. Now, when I look through your bio, you … If someone was to take my bio, and just swap out the things for different things that were kind of similar, that would be your bio. You have this passion for movement and cross training that very few … admittedly a growing group, but still a very small minority of martial artists have, and I love that. I know we're going to get into some cool stuff, so I’m pumped that we could get together.

ML: Thank you, thank you. I'm excited, too. I think that there's just so much knowledge. There's so much to learn, and everything is just so interesting, and I respect all kinds of modalities. I feel like cross training just gives me a better view of every game. I cross train a lot because at first I was finding myself. I didn't know what I wanted to do. Specifically, I didn't really like being violent. Violence was hard for me. I was very shy. I was an introvert. I was many things that I'm not today due to all this training for so many years.

When I got into it, I was like, “Okay, I just want to learn how to punch. I want to learn how to kick,” and then you can look at any martial art in different levels as you get older, and you can look at it from how to receive impact. That's something people don't think about, but that takes you a long time to learn, how to receive impact, how to take heavy energy, someone really going at you and you're not losing your mind but understanding how to think through these situations, emotional handling, and there's physical handling, and there's different aspects to everything.

I'm a lover, devout lover of capoeira, and capoeira is very fast. It's too many things into one, a whole culture in itself. Throughout my training of other things … Nowadays … I've been training capoeira since 1998 now, which is amazing to me that I can even say that. I trained in capoeira for that many years. It's exciting. It's also good and it’s bad, because I see everyone who started who's not here anymore, who's not here anymore. A lot of people don't make it through the funnel, the tiny little funnel, you start way up there, and then as it gets bigger …

JL: I would be one of those. I started capoeira in 1998. I made it about two years.

ML: That's amazing. That's amazing. See? That's what I'm saying. It's a funnel, and capoeira is vast. There's too many … Capoeira doesn't really have rules on how you can use your movement. Pretty much there it is, and that's a difficult thing for the capoeirista themselves to understand. You've been in the game for that long, you can see how capoeira is not … It's not like jiujitsu. In jiujitsu, you're going see a little bit of a variation in style, but jujitsu is still jiujitsu. Boxing, you're going to see a variation in style, but boxing is still boxing, but capoeira will still be capoeira and it will look completely different, depending on where you go. The more I traveled, the more I saw that it was different and different. Now, later in the game, I'm starting to understand how to join things, how jiujitsu fits into capoeira, capoeira fits into jiujitsu, and how my slips that I use when I train boxing are good for everything, for movement for arm drags, for takedowns.

JL: When you talk about … You brought up those three arts: boxing … When you say jiujitsu, you're referring to BJJ specifically?

ML: Yes. I am a first-degree black belt in the art of Brazilian jiu jitsu as well. I started training jiu jitsu a little bit after I started training capoeira. I started capoeira at 14. I started with karate at first, at 12, and then did kickboxing, did Muay Thai, did everything I could get my hands on, and then, when I found capoeira, my heart just beat different, you know? It just …

JL: Oh. I like the way you said that.

ML: Yes, because amongst capoeiristas, we say that capoeira, it picks you. It chooses you. You don't pick capoeira. It picks you. You’re meant for it, and you fall in love with it. Like I said, it's so vast, you keep … The more you learn, the more you notice, you have so much to learn.

When Brazilian jiu jitsu came into my life, it's because I was getting … I was extremely bullied, and as the person … Back then … The little kid in me could never imagine the woman I am today. I always remember being that little kid, being defenseless, being helpless, not knowing what to do, because I was getting beat up on the daily. I lived in upstate New York, and everyone thinks that upstate New York is great, but it was so ghetto.

JL: Depends on the area.

ML: Yeah, it was like a little tiny hole ...

JL: I'm not going to name names, but I've spent time up there. I'm not that far from upstate New York. Depends on the area.

ML: Upstate New York was different for me. We moved to the States when I was … Well, I was born in Brazil, so I am Brazilian American. I was born in Brazil. We're going way back. I was born in Brazil, next to the Amazon. I'm from Belém do Pará, which is different for most Brazilians in the US, which is why I look Hispanic, and everyone will speak Spanish to me, but I'm Brazilian.

JL: I've heard that is the worst thing you can do to a Brazilian is to speak Spanish, because it's so frustrating. Very few of us learn Portuguese. I can still count to 10. That's all I've got left from my time in capoeira. If I was to rattle off some Spanish at you, I've heard it's like nails on a chalkboard to someone from Brazil.

ML: See, but that's where I'm different. I'm fluent in a couple of different languages, and I spent time living in Puerto Rico, so I got to emerge myself into culture a little more. I'm fluent in Spanish and I’ll speak Spanish back, because before I would get that feeling, but Spanish was the closest language I had when I came to the States. We went to Miami. It was easier to learn Spanish than it was to learn English, so I started learning Spanish. Miami was interesting, too. Miami is so warm, so full of culture, and coming from Brazil, at the tender age of a couple of days to turn to 11? I came during the World Cup of ‘94.

JL: Why don't you move? Why did your family move?

ML: We were very, very poor. My life in Brazil, the time I spent there was also difficult. We lived in the gold mine for a year or two, digging up gold. My mother was always working, and she was never home. I have brothers, so I had to grow up very early. If you see a child in Brazil and a child in the US, the child in the US is innocent longer. You see a child in Brazil, they understand a different view of the world, the view of the breadwinner. They work hard, they have to contribute. They have to … It's just different. The world is more malicious, for lack of another word, because people don't have a way, so they have to watch out. Watch over your shoulder to make sure no one's trying to steal your money when you're going to the market. It's different.

When I came to the States, it was freedom, in a way, because we had a lot we didn't have. We were so poor that sometimes it was like, “Okay, rice and beans. This is what you have.” At some points, my grandparents hunted, so they brought back meat, and then we had a lot of meat for a while. Things were tough. Things were always tough. That's all I remember when we were a child.

JL: You hinted at something at the very, very beginning, and it was an interesting word choice. I don't remember exactly what it was, but it gave me the sense that you grew up around violence. Was there a violence component to your time in Brazil as well?

ML: Yes, there was always a violent component. Yeah. Growing up, you see a lot of abuse. It's normal. Men beating up women, it's normal to see that. It's not normal, but you grew up a lot around that. People in my family … Seeing that happen when you're little puts it into perspective, like, “Well, if I don't do the right things, maybe I'll get beat up,” which happens. Over there, whenever you did something wrong, back in the day, you just deserved a really good spanking.

Then my mother, who didn't know what to do, was a child with a child, when we grew up, I just, I got beat a lot in the beginning because it took her a while. She's an amazing human. I love my mom. I know she did what she could. I have nothing but love for her and the woman she helped me become, but when you're going through that, you don't know how to handle it. You don't know what's right, you don't know what's wrong. You end up becoming what you're not. That's normal nowadays, for people to become what they're not, and for people to be okay with that, to be what they're not. You go through life being what you’re not, being expectations, being what you're meant to be for the family. In Brazil, when this is your reality, it's much more in your face that you have no other choice but to help.

Coming to the states, having younger brothers meant I didn't have time for sports, because sports were right after school, but I had time for martial arts, because martial arts training is always at night, so there was time for martial arts. I was like, “Okay, I get to practice something. I get to learn how to protect myself.” I didn't know how to punch. My skills were kicking a soccer ball really hard. I played ball. I've always been an athlete, but hitting someone, it's something I couldn't picture myself doing back then, being violent. You end up being violent because your environment will ask you for it. Not just in Brazil, but then moving to Miami. I started getting into fights, and then moving to New York, I got into more fights.

I said finally, “Well, I need to learn how to fight because this is crazy. I can't be living my life this way.” When you're young, your mind is so easily manipulated by the good things and by the bad things. Then you start thinking, “I'm not meant to be here. I'm so depressed, I can't go out of my house.” It came to a point where I used to go to night school because I got beat up so much during the day that I had to go to night school. Then finally, my parents were like, “We're done,” and then we moved to Massachusetts from New York.

JL: How old were you then?

ML: Fourteen.

JL: That's when capoeira started was in Massachusetts?

ML: Yes. In New York, I ended up training karate, so I learned basic punching, kicking. I enjoyed it very much. I understood what it was like to hit hard for the first time. I think that was a very pivoting moment for me as a person, because I felt empowered, because I didn't know that I could kick that hard, or punch that hard. I remember the teacher going, “Don't kick anyone like this out in the street, please.” I was like, “Really? Why?” He was like, “No, you're doing very good, but don't kick anyone like this in the street.” I was like, “Okay.”

I used it, of course, when I have to protect myself from my nature as a caretaker, but at that point, I was already reactive. I was like … If anyone said anything, I was like, “You want to fight now or later?” because you get conditioned. If I show fear first, that's it. I'm done. I'm done. These kids are never gonna leave me alone. If I show signs of fear, they will chase me to the ends of the earth. I am good.

Then, when we moved to Massachusetts, it was different. I remember my very first day of school, my very first day of school. For me, in the school that I was, there were a lot of cultural differences. Half of the room was Black and Puerto Rican. The other half was white. On the side in the corner were all the people that came from Latin America. I was very … I knew I didn't belong, because I was the only Brazilian. It was like, “Where do I sit?” I sit here, I got in trouble. I sit there, I got in trouble.

JL: Where in Massachusetts were you?

ML: No, that was in New York, but I came to Massachusetts afterwards. No, that was New York. It's called Ellenville.

JL: I don't know where that is.

ML: It is 30 minutes from Middletown. You find Middletown on the map, 30 minutes, real upstate, literally, a hole in the mountains, and there was so much violence. A lot of my friends that stayed there, they just … they didn't make it. When you think about people not making it, you being that young, it's weird. It's odd. It's like something that's not meant to happen.

When we moved to Massachusetts, my first day of school, I remember – and again, this is from my ignorant eyes at the time, from the reality I lived in to the new reality – I saw a very dark skinned man speaking … He said these words exactly. He went, “Oh, my God. Today, it's wicked cool.” I was like, “What did you just say?” Again, this is a cultural difference. I was just like … Then I saw a very light skinned blonde girl going, and excuse my language … I'm not even going to say it, because it makes me spike when I say it, but she was like, “Yo, dog,” and used the “N word.” I saw …

JL: Hmmm.

ML: That's what I'm saying.

JL: Those are some interesting contrasts, and you said this was your first day? You don't even know what to think, you're just, “What is happening? Is this the upside-down world?”

ML: Yes, but then, a huge Brazilian community … which was also hard. I didn't know how to deal with Brazilians. I just came from learning how to be American. The only reason why I don't have an accent is because I was working really hard to sound American for a long time, being in front of the mirror, speaking to myself, making sure my “bathroom” sounded like a “th” and not like an “f.” You know? “I have to go to the “bafroom, miss.” Then you come and you're not Brazilian enough. You're like, “What? What happened? I thought I just went through this backwards over there.” Then you come here, and then … I didn't know that people were so culturally different in Brazil because the places I traveled in Brazil were all in the north. People aren't that different, but then even if you go from the North, and you start going to São Paulo, Rio … and then you go to the south, it's like different countries. They speak Portuguese, but it’s so different.

JL: People forget. You know, but listeners may forget how big Brazil is. It is not a small country. It’s massive.

ML: It's massive. It's huge, and there's so many cultural differences within Brazil. So much is different, and the people in Framingham are mainly from – because I moved to Framingham – people in Framingham are mainly from Minas Gerais, which is a completely different dialect of Portuguese than I have, so here we go again. It's okay. You keep going.

Then I found capoeira, and then I was like, “Wow, this is so cool. This has dance, this has music,” and I was doing a little bit of ballroom. I've always liked to dance. I've always liked everything, so I figured I'll just keep myself active in the time I can, because every other time I was being a caretaker to my brothers. I figured I'd enjoy the little bit of time I have and always explore. Then, when I found capoeira, it was like, everything was there. Then in our capoeira school, a couple of years later, when I saw jiu jitsu, I was like, “That's a really tiny woman handling a very big man.” It was amazing for me to see. She was just doing a presentation, but this presentation that she did, showing techniques and showing … She did a couple of sweeps, and armbars, triangles, basic jiu jitsu stuff from the self-defense situations, like chokeholds from the ground, and situations that I had been in, you know what I mean? Through feeling violence from other people. I was like … I didn't know what to do when that happened to me. I had no idea what to do, because what are you going to do? I was training karate. My punch is not going to be that strong in close range. Maybe it's not going to be that strong for some people who are really strong, period. Maybe it won't be as effective, because you're going power against power, unless you're really good, really comfortable, you're at a point where you understand movement, and you know how to dodge and how to get in and get out. Something I did not have yet at all, so I couldn’t count on it. I was like, “Okay, this doesn't work,” but then jiu jitsu. I was like, “Oh, okay. So interesting.”

I started training no-gi. I was like, “Wow.” Then, my capoeira master …

JL: Who … If I may ask, because capoeira at that time in Massachusetts was not big, can I ask who you were training with?

ML: I started in another group, [00:22:58] Capoeira, with, at the time was [00:23:03], with Mestre Boi. Mestre Boi went to [00:23:06] afterwards, but back in the day, Mestre Boi was in Jersey, [00:23:10] was here, but then I had happen what many of us have happen in martial arts, my master up and left. He just bounced. We woke up one day, with all that love for capoeira in our hearts, and he got up and he bounced. It was so very difficult to have all this love and not know what to do with it. I met my Mestre, which is currently until today. He’s Mestre Ze Com Fome, which … “Ze who has hunger.” That's what it translates to.

JL: I don't know his name, but please continue.

ML: My mestre and I are the representatives for our group in Brazil, which is … I’m from a very large group. It's FICAG, the letters F-I-C-A-G, and it stands for Fundação Internacional Capoeira Artes das Gerais, because it also comes from Minas Gerais, from Belo Horizonte, my group coincidentally comes from Belo Horizonte. I met my mestre at my batizado. It was at a small event. Do you remember the Dragon Lair in Framingham? Still there? They had a bunch of events?

JL: We’re going back far enough, no.

ML: Okay, they're still there. The Dragon Lair used to have tons of fighting events at Club Lidos. They had some small competitions too, and they're still up, they're still standing in Framingham, and that's where a lot of jiu jitsu started at the time. We started jiu jitsu there because it was the only real jiu jitsu place, but they didn't do gi. They only did no-gi.

You have some guys in the area like [00:24:46], who's also a longtime Black Belt, [00:24:48] who's also a longtime Black Belt champion, all of them came … a lot of us from many different teams that are in Massachusetts came from the Dragon Lair at the time. We'd go to the Dragon Lair, train there, and then I'll go … My master will be a student at the Dragon Lair like me, and then together, we went to capoeira and I trained with him. Because he trained everything else, he did Muay Thai, and then he started teaching more Jiu Jitsu, and then he got into Gi, so I just did everything, because I was there to do everything.

At this point in my life, I was also an extremely reactive human, and being with other people was extremely hard for me. That's a fact. I didn't know how my … I didn't know how … Well, people easily impacted me, and I didn't know how I impacted people, so I didn't know I was very … You know how it takes us time, I think, sometimes for us to understand the external, or how people perceive us. I was always … I knew how to speak, how my mother spoke to me, and it was always in a very rude tone. I knew how to protect myself by staying away, which means I didn't know how to socialize. Then when people … You know how in capoeira, how it does, sometimes things get a little spicy, right? Yeah, for me, if things got spicy, I was already like, “Okay, it’s on. Let's go,” because that's the mindset that I was in, it’s protection, it’s fight mode.

JL: All of a sudden, that headbutt’s not a fake. All of a sudden, you're making contact.

ML: No, no, they had to hit me first. I was very precise about that, because remember? I still didn’t like hitting people.

JL: That's what I mean. They slip, that … I'm forgetting all my term names, but a kick connects. It's an accident. You're like, “Alright, let's go.”

ML: Yeah, because capoeira it really is, it’s because … Capoeira is in the subtleties, right? It's the difference between jiu jitsu and capoeira. In capoeira, we are very … it takes us time, but we learn how to maneuver energy and flow, and then you're always looking for that energy and flow together, but you are trying to catch each other. It's just that there's so much timing and exit, as you get good, the window of where you are able to actually get someone, it's like this tiny as they get better, because they have good protection, they understand how to use the movement to their advantage, and how to stay in the flow of the rhythm, because I think that's what takes the longest for you to understand.

Capoeira doesn't have rules, meaning I can kick fast, I can kick slow. The slow kick doesn't necessarily mean that it's a futile kick. Maybe the slow kick is a trap. Or maybe the slow … Yes, there’s lots of unsaid rules in capoeira. Because I had been through so many of these life experiences, and back in the day I started, it was still the 90s, so everybody was getting in, in capoeira. We had the street rodas in New York every Saturday. Have you ever been to those?

JL: Oh, cool. I haven't seen them in New York, but I've seen them in other places.

ML: Yeah, New York had … Go ahead.

JL: I've been tempted to jump in. Not now, but I bumped into one of them in Maine, of all places, and it was during the time that I was training capoeira. I was like, “I kind of want to jump in, but I don't know this group, because I don't know how they're gonna play, I don't know how they're gonna react to a stranger,” so I just watched. Yeah, I had just enough capoeira education to understand some of these things you're talking about.

When you talked about earlier boxing and you were talking about BJJ, there's the competitive aspect. There's the ruleset, which guides what people do and how they do, maybe not completely, but it does give some guidance to how things are going to go. The rules of boxing might be slightly different depending on where you go, but they're more or less the same. The rules of BJJ competition are more or less the same when you go places, but without being competition driven, capoeira can be so dramatically different, and what I noticed, and I'm curious if you feel the same, it's the personality of the instructor, of the mestre, that seems to make the biggest impact on the culture of that school. If the instructor is a big ol’ jerk, you can tend to play in a much more aggressive way.

ML: I think that is a reality of any art. The student unfortunately, because the student puts the master on such a high pedestal, we ended up just repeating the same cycle back and forth. Capoeira is very held into its traditions, but everyone argues about the tradition that is best, because there is an evolution of capoeira in different aspects. Like, we have groups that clearly are impacting other groups in their growth, like, I come from a more martial arts style of capoeira, but I know how to play the other games because it is necessary to know how to play all the games, but you can see clearly in my ginga what style I come from. It’s like a kickboxing type of stance.

JL: When you say more of a martial art style, would the other end of that spectrum be more the dance elements? Is that kind of a dichotomy?

ML: The reason why I say particularly a martial art style, I will still be dancing my bum off in capoeira because it needs that rhythm. The reason why I say a martial art style, I'm always worried about the malicious part of the game. Meaning, everything I do, I worry about the consequences, the action and reaction, which is something that we do as martial artists across the board. We always make sure that our base is one where we're not going to be leaving ourselves open. I do all of that within my ginga and in my movement. I always anticipate, as we do in other arts, anticipate what could go wrong.

The difference between my capoeira and other capoeira’s meaning is, someone who's from another style, maybe they'll prioritize a body language that has lower arms, more exposed face, and they trust their partners enough to do esquiva where their face is going to be exposed, right in there. Where, in my house or in my tradition, if you do that … In capoeira , we talk a lot about Malicia in capoeira, the malicious aspect of capoeira. Capoeira is supposed to look like a dance on purpose, so it's meant to make you comfortable. Capoeira is meant to make you comfortable. It's meant to make you free, meant to make you get into my flow, like the old snake dancing around tricking you, until the bite comes. We talk about that a lot in capoeira, that we cook the energy and we make things happen, just like in BJJ. I'm small. I can't go head to toe against a guy who's bigger than me, but we put a kimono there, things change, because I have a lot of tools, because I understand my grips, the action and the reaction, but I can't make him do what I want. Not exactly. I can't push him and he won't go, but if I pull him, he will go.

Capoeira teaches you a lot of this getting in and out, and you're supposed to be thinking about this 24/7, but I come from … There's many different styles of capoeira, many different styles, but capoeira that was created by Mestre Bimba, which is the Capoeira Regional, the capoeira that comes with more of the fighting aspect, the capoeira that’s a bit more athletic and dynamic. Angola is also dangerous, and it has the same use, but it is slower. However, I think Angola is very dangerous, because it's the little things you can't see.

I think what's happening now is that a lot of capoeiristas are losing the aspect of the martial art of capoeira, meaning attentive to action and consequence, action and reaction, understanding that it is a martial art. We are meant to have a stance that's going to be hiding our vital parts, all of these things that are supposed to be primal to the art, because that's what it was created for. It's an art of liberation. Capoeira was created in a time of need, of liberation, created by the Afro-Brazilians, so the African slaves that were taken to Brazil, that were going through struggle, that had no liberty. Capoeira was created to look like a dance because when the [00:34:11], or the slave owner, would be like, “Oh, they're just doing their tradition,” but no, they were fighting. They were practicing. A lot of the movements are called animal moves because they were getting ready to rebel, to liberate.

I feel like losing the martial arts aspect of capoeira is almost an injustice in my point of view, but what I mean about the other side is the other side is … they're more worried about maybe the aesthetic part of capoeira, or what it does for your body, and how it looks visually. You know what I mean? You see some people, they will kick very wide and they will do very pretty things, but then there's no attention, but the person who's good at capoeira, truly, there'll be doing a backflip, and in midair, they're still looking at you. In midair, they're still watching you, because they understand they just did an action, there's going to be a reaction somewhere, and the consequences are always there.

In the Capoeira world, as a woman, I'm going to say right now, and the capoeiristas who are listening will truly agree. As a woman in the Capoeira world, having a game like mine is very different. It's not very usual, because capoeira is vast. Capoeira has takedowns, lots of takedowns. Lots of takedowns, lots of action-reaction, ins and outs, lots of maneuvering of energy, you can make … It's just like boxing and any other art. You're not going to go and just punch in the face if you want to punch in the face. You’re going to punch in the body until the face is … liberated. You're like, “Oh, the face is there now. I’m going to go to the face.”

In that theme, that's something that training martial arts, cross training in martial arts, it's just a different view. One thing that I don't like to get into even though I cross training into other arts, I keep capoeira capoeira.

JL: Is that difficult?

ML: I think for me no, for a lot of people it is. For me, it's not difficult, because I exercise it often. I work on my body language diligently. I'm always working on my body language, and I'm always trying to make sure that there's a softness, but it's open to other things, but what's happening right now in a lot of social media … which it stinks that's all people care about sometimes is being famous. It’s sad.

JL: We all know it gets you almost nothing.

ML: I know. What’s the point? But they're doing it. They'll be doing like, “Oh, capoeira’s good for the body,” but then the girl’s wearing gloves, or the guy’s wearing gloves, and they're punching pads, and then they're doing kicks. You’ve seen that video, right? They’re punching pads.

JL: I've seen a number of things that purport to be capoeira that … I fully admit, I know virtually nothing. I can step into it a roda and barely function at this point years later …

ML: Oh, stop. Stop. Stop.

JL: … but I know enough to know, why are you wearing fingerless gloves? There's no point to that.

ML: It’s like I said, it's different views of the game, you know what I mean? Like, I can go in capoeira, right now, I can go into capoeira, and anywhere that I am in that roda will give me what I want from capoeira, because I'm there to take the energy. Obviously, I want to play, but there's ways you maneuver the game so the game is down to your level. If you're like, “Okay, I really don't want to brawl because I'm not feeling good today. I don't want to get in there and do all that.”

If your body language, which as I said, I work on body language diligently, because there's a difference between me doing a ginga with my upper body and things are relaxed. Like, “Ah. Hey, let’s play, okay.” If you see people, they want to play because it's loose movement. You can tell that there's no ill, but if I start going … [demonstrates technique] … there's a lot that's going on, and that took me a long time to understand. The fact that I understand it is a victory in itself. It's understanding how to keep the energy where you want it, understanding that how you get in there and makes the difference. Let's say, if I was in your shoes, I'd be going to, “Who does the roda belong to? Oh,” because this is how I learned.

I was very fortunate, and I'm going to say fortunate, because not everyone gets this anymore. How do you get to a place? How do you go somewhere? How do you go somewhere where you're not known? You're the only person. How do you not mess up what's going on there, but still play because you want to play so bad? Usually I would go, meet the owner of the roda, contribute with some energy and say hello to the people who look like them. They matter. You can always tell, the people who matter. You can always tell. “Hi, how are you?” I’d be like, “Can I play?” “Okay,” and you breathe, and you smile, and that took me forever to learn how to do it. You smile. You SMILE. That's why capoeira is called playing. It's not called fighting, because your face can change so much.

In the beginning, when I played, I always looked angry, because that's how I felt. Now, I put a smile on your face and you let the energy be slow. You don't have to play lots of capoeira, or you do, but lots of capoeira can be looked at differently. Lots of capoeira can be moving and really feeling what it's like to be in your body during that moment, because the roda is like, wow. It’s people, it’s energy, people are smiling, people are clapping, people are playing, the instruments are there. If you feel that for capoeira, that you want to play, you're like, “Oh, that's amazing. I'm going to go play.” We call it that the berimbau, it calls you. Capoeira calls you to play. It invites you for a dance, and then how you enjoy that dance could be so much. It's your own experience. I've seen people. Yeah, I've seen people who are so much older, they're in their 70s, and they're playing capoeira, and they will have amazing games. It won't be visually like, “Wow, they did a backflip,” but you can tell that they understand the game. They're cutting off movements, by just moving in a particular way. They're smiling, they're enjoying themselves. That's what I want this, this is my goal for what I do is being in the game until my time is over. Yes, until my time is over. Being in the game until my time is over, however I can't contribute.

At first, I wanted to just be good. I got into the roda, and I was good, and I got into a lot of fights, and I got known, because this is what capoeira was about back then, but what capoeira really needs to be about, which is what it's turning into, especially in the States … Look, you have a Brazilian telling you this right now. Brazilian, okay? I've been to Brazil to train capoeira. I train online with groups in Brazil all the time, and I speak to a lot of people. The capoeira is growing so well professionally in the States. People are doing it well in the States. They're doing a family environment. They're hitting communities, they're giving people the power of community, which right now, it's the most needed thing.

JL: For sure.

ML: COVID was hard, right?

JL: It was.

ML: It's still hard.

JL: Very true.

ML: Yeah, it's still hard, and a lot of people are very scared, and a lot of people have lost touch with themselves. And throughout this whole process of everything happening, I was like, “I want people to stay in the arts.” Like I said, I've been through a lot of things, but at this moment in my life, at this exact moment, I'm on the other side of a lot of struggle, because my husband and I were apart throughout my pregnancy and a couple of years, and we just moved back in together. He was in another country, and that's how I know Bernadette. Bernadette, me, and my husband.

By the way, I'm going to say this here, and if she hears this after, it will be amazing for me. Bernadette is the woman, the idol I needed in my life.

JL: How did you meet her? Tell us more about how you met her.

ML: She's my husband's friend. She's a black belt for Renzo Gracie, and my husband had a gym in Manchester, New Hampshire, so I was in Manchester, New Hampshire. We were Team Link New Hampshire back then. We were part of Team Link. Bernadette would come to train with us all the time. I was a blue belt when I met her, and I was competing a lot, and I was so in shape.

JL: You thought you were hot stuff, and then you rolled with Bernadette. Is that what happened?

ML: Oh, yes!

JL: Because you would not be the first person who said that to me about the first time they rolled with Bernadette. They were like, “I thought I was pretty good, and then I rolled with Bernadette, and I was like, ‘I guess I'm not.’”

ML: Like, “You're fine. You’re fine. You did great. You did great, darling. It's okay. You did great.” Then we’d go again.

JL: She’s incredible.

ML: She is, and for me, and I'm saying this as a female martial artist, and I've been in the game for like … when I met her, I was already in it for a while. It is so difficult to have someone to look up to that’s going to be that close. You're going to have people who are far away now. With social media, you know about everybody, but to have someone that close, someone I can talk to, and I was … Not just that, I was very angry still. I was very angry, and she's like … She used to tell me I was very closed up, but when I saw her, I would talk a little more. She would always get a little more out of me. I was like, “Kind of scary, but kind of cool.”

She loves my husband. They're great friends, and she came to train with me many times. I trained with her through my purple belt days, got my brown belt. We would meet each other often. We're friends, but she was close to me in a very important moment of my life. I had gone to Seattle, Washington to teach a capoeira seminar for a women's capoeira seminar, which I'm always passionate about helping more women stay in the game, because I think this is what I'm here for, to do it, empower others to do it with me, and that's what I want. I don't want to be only me, I want to have a crew. That's what I'm about. I know, it's weird saying that, but it's about time. I want to have a crew.

When I came back, my husband was supposed to pick me up at the airport. He wasn't home. I went to the house, and he wasn't around. Mind you, our wedding was already booked. We were going to get married. I was already an American citizen, and he was caught by immigration. Yeah. I was running the gym by myself. I was going through so much struggle, but pushing it, pushing it, and no one saw me struggling but her. The only reason why I'm not crying right now is because I saw her a couple of months back, and I cried for like half an hour straight, because she's like, “No, no, let's slow down. Let's slow down. Let's talk. How are YOU doing?” You know, to have someone ask you how you are doing, genuinely … People are like, “Oh, your husband …” because it was all his students, people who cared about him. The city, everyone was very … Everyone was impacted …

JL: They’re questions to you were about him? It wasn't about you and what you were struggling with?

ML: Yeah, it's not just the questions to me, but I was put in a place where they expected me to emotionally help them, and I didn't have that. I didn't even know how to help myself. I couldn't help other people, but I kept trying, and I ran the gym for a while, and then finally, it didn't work out, so he ended up going to Brazil. Then that's where all the traveling happened. Like I said, the other side of the struggle, because I'm just back in the States now, after all of that. It's been a little while. My husband just got back in December, he finally got legalized.

JL: How long did that take?

ML: Since 2013.

JL: Okay. Nine years.

ML: Yes, but then through that, we got to go through Brazil, so I got to train in Brazil and learn about that, and then understand myself culturally, too, because, again, it's like, not American enough for the Americans, not Brazilian enough for the Brazilians. Then I moved to Abu Dhabi to work on the Brazilian Jiu Jitsu project there. I worked there for a couple of years, and it's the only place we could be together. Bernadette was just always, always, always, like, always checking on me, always. When we got back, she made her way to come and see us right away. Just see how she does things, and how she does things a little different, how she cares more about the human. Where I come from, old school style training, where you … This is how you get good, you're kicking tires, and you're pushing your body to the limits, and that's not what it's about, but that's what you think it's about in the beginning, right?

Then, being this far in … Over there, I got to train with all women all the time. That was very difficult for me. Not even going to lie. I didn't even know how to deal.

JL: Why?

ML: Because most of us all women that were there training with all women had never trained with women before. Because it's all in the black belts, black belts. Most of them are the black belts, the old school black belts, but the new generation is still coming in, so a lot of them didn't have to share the mats with other people the same. They did, but not the same. Over there, it’s like, I’m one team. You're another team. He's another team. We all compete for the same company. We all compete for the UAEJJ Federation. When we train, we all train together on the same mats. Then at some point, because it's a Muslim country, they would seclude the trainings, women can only train with women. That's hard because we're emotional. It's hard for all of us. It wasn't just me. It was all of us. All of us struggled through it. All of us didn't know how to do it. All of us messed up. That's important to say, all of us messed up, meaning like we treated each other badly, we were the human we realized we didn't want to be, and then you evolved.

JL: I was hoping you were going to say that, because if not, I was going to ask. Can you talk about that evolution and what that looked like?

ML: For me, in the beginning, just training, just … As a competitor, when you compete often, you're one mindset is you have to be better than everyone else in the match. That's how it is. When you're competing, you have your sponsorship, and this is what you want to do, and you put your mind that you want to be the best. That's how it is. Being with other women that are good, and better even than you, is very difficult, not just for me, but for them, because when I got there, I was also a brown belt. That was difficult, because brown and black were put together. For the women to train with me, it was hard, because then someone would always go there and be like, “Oh, that brown belt beat you up,” versus … A good, well-trained purple belt will be as tough as a black belt. That's the reality. They're going eight-minute fights. It's crazy. They will be physically prepared, just as prepared.

Then a lot of us started building families, a lot of us are around the same age, a lot of them older than me. I'll be 39 now in July, and a lot of them will be even older. For me to be able to see them growing … Then you have women who were part of the Olympic teams. You have like Olympians there. What is it? [00:51:42] The only athlete, not man or woman, the only athlete ever in Brazil to go to the Olympics for two modalities at the same time. She went for judo and for wrestling. This is amazing. Then you have what you see them becoming Moms, you see them going through the process of … you're getting pregnant, you're on the mats, you can't train, you’re body is not the same, then coming back, feeling like yourself again, because when you're an athlete, and this is how you use your body, and you’re a woman, a pregnancy is difficult. It is a blessing, but it is difficult. You don't have the same … It's not the same. It's not. You don't have the same power, the same muscular engagement, none of that.

This doesn't even really have to be a woman, or a man, or pregnancy, or postpartum. It's more about at some point of your life, you're not going to be this amazing athlete that you were someday way back then. I think that's the hard truth to come to terms with when you're in this game for long enough, and you have to go through life staying in it, meaning you go through pregnancies, you go through marriage, you go through changes of lifestyle, of work, you go through age, you go through injury, which is why I deal with injury prevention specifically. That's what I do for work. I built my own company, and I decided after all of that …

JL: Yeah, talk about it.

ML: Yeah, so this is my company here. I'm repping for myself.

JL: Not everyone's going to see this. Most people are actually going to hear it, so make sure …

ML: It’s okay, I'm going to describe it. I'm wearing this amazing tree.

JL: It's a cool shirt.

ML: There’s lungs at the roots. These are lungs, and a uterus. There's a uterus in there. I know. I know. The reason why I have this is because I started learning breathing, and I incorporated breathing into my life as I was going through the struggles. Remember, I had to come. I had to leave my husband and my life that I had in the UAE. In 2018, the law changed, so I had to come to the States and be here, pregnant, and it was difficult, and I wanted a natural birth. Through my research, I started getting into Hypnobirthing, which has breathing exercises. I did it. It was amazing. It was also very painful, but amazing.

JL: That’s really cool. I can only imagine.

ML: No, but I felt good about myself because I wanted that moment for me, for my husband, for what we were going through, for our amazing daughter. We do… I have a 14 year old and a three year old. I was okay, as I started to practice breathing and I couldn't get back … Like I said, my body had just gone through that change. I couldn't be the athlete I was, so coming back postpartum is very difficult. So I began investing my time into breath work. Lots of breath work, lots of research. Then I started studying physio-training, which talks about healing the body organically or a more holistic approach to injury prevention and healing of injury. I started becoming a trainer and just getting out there and training more because I couldn't leave the house. I was pregnant with the kid, so I had to be home. This was my reality. I went from being an athlete, being a BJJ coach, I was doing tons of things. I was doing TV work, I was doing breath things, and then suddenly, I had to come here, and now my reality was being a housewife, without my husband, though, because he wasn't here, so a single parent, pregnant. Cool. How do you do that? I have no idea, so you figure it out as you go along.

This came to me as this process started happening. The reason why I have a tree is because it reminds me of resilience, because I had to care for others. At first, I was like, “Oh, I only have to care for others, care for others, care for others,” but then I realized that what I really needed to do was care for myself. I didn't care for myself, I couldn't care for others. It's like the airplane thing, you put your mask on first, so I started putting my mask on. Then I started believing … understanding myself, and getting into my mind, and being with myself more. Meditation came after, so many things came after, but that big mirror was right there. Then I could see all the things that I wanted to change, because when you're responsible for … even if you're a teacher, you don't have to be a parent, but when you're responsible for influencing other people, that's a lot of responsibility. That's very heavy.

I started working with myself, and then as I went along, I realized that we all have seasons, which is why I have all the colors, we all have seasons. I needed to understand that my body doesn't train the same 24/7. I don't train the same 24/7. Some days, I train great, and I ate great, and I feel great. Some days I was sick, and I felt horrible, or some days I just don't feel right. Some days, it's just not my day, but you know what every day is? Every day is a step towards the future of you staying in the art, and being resilient means having consistency, it means listening to your body.

Think about it. Nowadays, the lifestyle we have, we sit. I'm sitting with you right now. We're sitting, and we sit most of our days. We sit all day, most of our kids are “text neck” all day looking at the phone, then we have very bad breathing patterns because we're always in a fight or flight mode, because we watch the news, we feel some kind of way, we have interactions with people who don't accept us and we don't accept them, then we feel some kind of way. We don't even take time to understand what's going on with ourselves. Half of you have being good at martial arts anyway – not even half, way more than half – is knowing yourself and your capabilities, what you can do, what you cannot do, and the things that you don't like, how you can change them for the better in a positive way?

I built this company out of a dream, and the more I find myself in martial arts, the more I understand that now, it's not like back then. Now I have life experiences, and these life experiences can help me to help others help themselves. Not a lot of people do that. A lot of people do do that, but not as many as there should be.

If you think about it, people are just worried about the next news, the next exciting thing, the next TikTok video, or what did that start do? Then I find myself being able to put my phone down, understand that I need to be stepping on the Earth every day, I need to be breathing fresh air. I need to be spending quality time with my children and the people I care about because life is so fleeting, so short, incredibly short. Because I want to be in this for a long time, it really hurts me to see people leaving, and people leave because they lack support.

JL: Hmm, say more.

ML: People leave because they lack support because a lot of times, it's like you said, it's all about the teacher, and it is all about the teacher. Like I said, we end up repeating past things, which is why I'm redefining it, so I'm branching out of my programming. We’ll say that. I'm branching out of my autopilot and I'm using my masters and the masters that came before me as evolution.

My classes are all about the person. I want to empower them so that they can feel capable enough, to have an injury or to have a difficult moment, and to understand that they are capable enough to get through anything. We are all capable enough to get through anything.

As a woman, from my end, the support ends up going away as you get older. You get older and you build a family, how do you stay engaged? You're most likely not training with your teacher anymore, because you're probably teaching on your own, but then you have your family to take care of, and then we don't have a lot of the teachers reaching out to the teachers. Then that part is difficult, because … If you're seeing a woman come back from postpartum, it's natural. She's back. She's okay. Some women are great, some women are not. Some people have postpartum depression, some people feel secure in that environment. Some people don't understand or can't imagine having a life of practice that their body doesn't feel the same as it used to before not even just pregnancy, but any kind of traumatic experience in your life, because you're going to have them. You’re human.

Then you're like, “Oh, I injured my knee, but then it was so hard just being there that I just decided to quit. Then when I decided to go back, I always wanted to get in shape before I got back, but that never really happened. I don't like to get beat up, and that was difficult for me, so I decided to leave.” That's a reality, no one likes to get beat up. No one likes it, but when you're a martial artist long enough, or even when you're in capoeira – which is what capoeira brings you, you bring a smile to your face – you understand that at some point, if you just … Every experience is a learning experience, and when you leave yourself open to getting hit, it means that you did something wrong and they did something good, but they're just on their game. Go ahead.

JL: Talk about your classes. I hinted at the top that you do a bunch of these different things, and they're incorporated. We've talked about BJJ, we've talked about capoeira, we've talked about breathwork, but there's a bunch of other stuff in that mix that we haven't talked about.

ML: Yeah, so the tree is there, too, because I really believe in resilience. I believe in resilience. I believe that a tree should be flexible. Like I said, I believe it should go with the seasons. The style of lifting that I do is always unconventional. I use unconventional training methods to continue to use the body and the ranges that I should be using in mundane life.

JL: For example?

ML: For example, I will not [have people] hold a squat unless they really know how to use that squat. I make sure they understand proper engagement, so when they do lift weights, kettlebells, and … I use the kettlebell mainly, and steel mace. Those are my jams right there. That's my jam. The kettlebells and the steel mace, they take the body, the shoulders, the hip joints, all the joints through different ranges, while being loaded. The fact that they're unproportionate, the way they’re built is unproportionate, it tells you right away if you have any kind of imbalance. The kettlebell particularly will be always pulling your way back, forward, side to side, but the steel mace will be completely … Right away when you touch it … People expect the mace to be easier because it's light, so you're like, “Oh, I can carry it,” because when I started macing I could carry like a 20 kilo bell. I could press a 20 kilo bell when I started macing.

JL: Americans, that’s 45 pounds.

ML: Oh, sorry, 45 pounds.

JL: That’s okay. I can translate. I can't translate Portuguese, but I can translate kilos.

ML: I don't know my steel mace weight in kilos. I only know it in pounds. When I picked up my first mace, it was a 10-pound mace. I was like, “10 pounds, 45 pounds, 10 pounds, no biggie,” and the first time I touched it, immediately I can see my body going into alert, because it was off balance. I couldn't keep the thing straight for too long.

JL: That’s a long handle.

ML: I know. You see people doing it, even through the switches, it stays so straight, the muscles are so engaged, and you're like, “Wow, that's amazing.” By then, I had … When I started unconventional training, I was coming back from the pregnancy, COVID hit, I couldn't go to the gym anymore, I didn't have a sitter. What am I going to do? I need a weight lift. For the women that are listening to this, if you don't weight lift and you're getting older, coming back postpartum and being without access to a gym at all … Downstairs, we just had these really … We had four kettlebells downstairs in the basement gathering dust, gathering lots of dust. When I started doing kettlebell training, I was like, “Wow,” because I did some core conditioning as an athlete for Brazilian Jiu Jitsu. I always had a trainer to get me ready for tournaments, and we did the basics, the swings, the whatnot, and I thought I was doing them so well, and then …

JL: There is no movement that I see done in gyms that makes me want to go over and tell people to just stop more than kettlebell swings.

ML: YES!. Oh, my God. The American ones, they do them all the way up, and then they hinge the belly forward, and you're like, “What's going on?”

JL: I'm fine with that. It's the down, where they're just so rounded, and you can just see it. They're using one that's too heavy, and it's just … they're letting it pull their back down. I’m like, “Ugh.”

ML: It's difficult. That's what I thought, I was like, “Oh, I'm just getting into this. I'm going to get strong,” because I love being strong. I absolutely love being strong. I love being capable. It's important to me, for what I practice, because I like being good at what I do. I know that weightlifting needs to be a part of it. What I was saying was, as a woman, and like I said, I'm older now, I will be 39 next month, and as we get older, we start just losing bone mass. The only thing that is proven to change the bone is weight-bearing exercise. I have a lot of female clients that will be like, “Oh, I want to lift with you, but I only want your legs. I don't want arms like you.” Then you're like, “Do you know the benefits of actually weight bearing, gaining some muscle? It’s good for you.”

A lot of women are changing that, which is great. It's amazing. That's what I wanted for me. I just wanted to get strong, but then, I was at home and I was stuck, and I was looking for information, because … You know, the internet is so vast, so vast, and there's so much bad information out there about kettlebell training, specifically, because it's so popular right now. Everybody has a kettlebell at home, everyone. No one knows how to use it, exactly.

I started self-studying. I'm really good with watching movement. I have a really good eye for movement. I had already been perfecting that being the trainer already. I got a certificate from NASM when I was pregnant. Then I already started taking in clients and trying to see what style, or how I wanted to train. At first, I tried to do it how my trainers did it for me, because that's the only reference I had. Then I realized, now I remember why I hated the way my trainers did it for me, because it took too much time, and it was a lot of quantity over quality. It was supposed to be the opposite. They would be two hours at the gym. I was like, “Do they not have kids?” Who spends two hours straight at the gym lifting?

JL: People who like punishing themselves, or people who enjoy lifting.

ML: I enjoy lifting. I really do, but I will not lift for two hours. That's what I’m saying. This is what people think, that they need to be there for a lot, they need to do a lot. You can fatigue the muscle in less than an hour. It’s just how you do it. Then I got into the certification for Living.Fit, which is part of Kettlebell Kings. I consume a lot of information, period. I love to study, and I'm always reading a book. If I can't read, I'm listening to something. I'm always listening to a podcast. I'm always trying to have a different view of the world and be reminded that my goal in life is to grow, is to evolve, is to get better. I don't want to be the same person I was even last week. I want to be less ignorant than that person. I want to be more open-minded and I want to have more freedom with more information. Because there's so much information out there, what sucks is, most people don't know how to concentrate on the positive side of information, but that's what happened for me. I was able to concentrate on the positive side of information.

I was researching breath work. I started researching kettlebells. I got my certification from Living.Fit, the expert certification with a test in the end, very proud of myself. I started training people in kettlebells, and that was great. Then my friends were part of TACFIT. Have you heard about TACFIT before?

JL: No.

ML: Tactical fitness? TACFIT is a fitness system that actually helps you rejuvenate the body, stay in the game longer, pretty much everything that I was already doing.

JL: Cool.

ML: It's called the VKNJA [Viking Ninja] system. I'm a Viking Ninja. That’s the name of my certification.

JL: Nice!

ML: I know, right? It's pretty cool.

JL: That’s pretty fun to say.

ML: Yeah, like, “What are you?” “I am a Viking Ninja.” I got certified in that, and it was a grueling two days, two-day online course. Again, throughout this whole process of learning, of studying, of all these things that I was doing, I was with the baby. I was a full time mom, full time breastfeeding, full time, throughout that whole thing. When I had to train prior to COVID, the kids were coming with me. When COVID hit, I can only train … my consistency was once a week for a while, but that's all I could get. I'm not going to take it for granted.

JL: It’s better than zero.

ML: Exactly, and when you look at a growth chart, if you zoom out, like a couple of years out, you could still see growth happening, and I was like, “No, I need to stay. I need to stay consistent, because if I stay consistent, things will happen,” because pregnancy is very difficult. The returning process is difficult. Throughout that, I had to learn how to ask for help, and I had to learn how to rely on help. I had to relearn how to be kind to myself, enough that I understand that I need those things, that it's okay for me to ask for help.

I left my daughter with my cousin. I borrowed my friend’s capoeira gym, and he let me be there for these two days of cert, and then I passed the test for the VKNJA system. I was like wow. Then I started playing with these two modalities and body movement. It all just became one, but instead of thinking about just the exercise aspect, which is a difficult aspect. Exercising, weightlifting, it's accessible from home. Great, but then there's also the most important part of it, which it will be the neurological connections that you make, and it will be how you think, or how hard you think, how you think of consistency. How do you fit that in your life in a way that's really going to stick, versus being something that you go really hard at, and then it gets really tiring, and then you really want to have nothing to do with it because it's annoying, now I don't want it anymore.

Being a martial artist, it's like that. We always have to keep it interesting and change our view, because there's always something to learn. Even when you reach the wall where you're like, I think I learned everything because you have those moments. You're like, “Yep, this is it.” When you're younger, in the arts, you're like, “This is it. Now I'm an expert, officially. Just give me a black belt, and I'm done.” Then, as you get better in the arts, you're like, “Wow, I literally know nothing. Nothing. I need to put my student cap back on and get in there.”

I try to work with people in a way that … the main part of my work is opening up, and I do other things like sensory of the feet, sensory of the hands. I like science, I love science, but the main thing that I do is have people open up a conversation and begin a relationship with themselves. I think that we're lacking in understanding ourselves enough to know how to learn, to know … not just how to learn, but how to teach. Teaching is so hard, because everything you lack is always right out there. The student will come up to you and will ask you something, you don't know about it, and then, you need to be a student all over again, time and time again.

People, they can't stay consistent, because right away, they're like, “Oh, that's it. I ate that burger. I'm the most horrible person in the world. I don't deserve to be healthy. That's it. I'm done. Oh, that's it. I got tapped out.” There are those moments, or, “I passed out.” That's worse. Haven't been there, but it's worse. “I tapped out, or I passed out, and I'm not going back because the young kids …” That's what's happening to the middle-aged people. The young kids are just too fast. “I can't be dealing with that environment anymore. I can't train there anymore,” like they don't believe in themselves. They don't understand. Then you're like, “Am I really seeing this the wrong way?” To me it's clear that we just need to love ourselves a little more. Right?

JL: Change the expectation. You mentioned watching 70-year olds play in a roda. No, they're not going to be pulling backflips, they're not going to have the most dynamic aesthetic movement, but they can still understand the game, they can still get better, and they can still enjoy it and better themselves.

ML: Exactly. You need to enjoy where you're at with what you have. Then as you go, you learn more tools, and then growth can happen in that space. I think the physical growth also comes from a lot of psychological and mental growth. If you're doing … Oh, like right now, you can't see it. I have a knee injury right now. I just hurt my knee last Friday, and I don't know what it is yet. I really don't know. I have no idea. Right now. I'm just babying it and tell it that I love it. “I love you. I love you, knee. Please get better for me.” That's where we're at right now. There's so many things that I can still learn that are outside of the physical body, and I can still do the physical body stuff. Yesterday, I isolated my knee, and I did a lift. I just did it sitting down. That's things people don't realize that they can do. In capoeira, specifically, music. Music takes forever to learn. Music is difficult.

JL: Just holding a berimbau is a nightmare.

ML: Exactly. Then let's think of the other level. Okay, holding the berimbau is a nightmare, but let's say you graduated from holding the berimbau, and you've graduated from … you know how to play it really well, to keep up in a roda. Singing. Singing is difficult. Let's say you know how to sing. Now, let's look at the perspective of singing from someone who's been in capoeira. Singing is literally the control of the energy in the roda. The emotion that you put through to your voice will make the game happen. I can make you excited, I can make you get beat up, I can make a ton of things happen, you know that. You know that. You've been in capoeira. You know.

JL: Yeah, I just like the way you said it.

ML: It's hilarious, but it's amazing, right? I conduct the flow of energy in the roda. With me, during my singing, I'm stiff, because it's hard to control your voice, because the instruments of capoeira, the reason why they're difficult to sing with is because they cross the … they don't flow with the melody. The berimbau will be like this, and then your voice has to do the complete opposite, but you’re still meeting at some point in time. Usually the percussion instruments are the first ones that people get into, because the berimbau … Yeah, man, because the berimbau is difficult. Then emotion, emotion into your singing. Being there. Being outside of the roda is work. Did you know that? Being a spectator. Why?

JL: Because you're contributing your energy, and just by observing it, your energy is involved.

ML: Yes, exactly. That's exactly it. People don't realize that. It's like a chain reaction. It's the singer, it’s the instruments, and because I spent so much time in the … In Abu Dhabi, I had to drive an hour and a half to go see Mestre Caxias, I was the pioneer of capoeira in Al Ain. They didn’t have capoeira, and being a woman …

JL: Cool!

ML: Thank you. I'm proud of that, because I was afraid to start because I didn't want to leave the students like I was left, but I started it and another mestre, a friend of mine, picked it up, so it's still alive.

JL: Wow. Nice.

ML: I know, and that's just such a gift to just plant the seed and have people build community around that. I lived so long there, and when the prayer starts, you have to stop playing. The prayer start … the prayer. It's a Muslim country. The prayer is numerous times a day. Being in this environment, I started understanding and having true appreciation for being in a roda where the people know how to play their instruments and where the people know how to conduct the energy. You know what I mean? It's just … it's magic. When you're there and you're like, “Wow, this energy is great,” because I spent a lot of time having to learn how to produce that energy. I did it. I realized when I started teaching that I didn't know how, and now I know how to produce it, but there's so much more I can do. Whenever I meet people that are higher than me at events, I'm like, “Wow, I really need to go home and play my instruments.”

JL: I love it.

ML: Yeah.

JL: If people want to learn more about what you offer with your programming, your coaching, teaching …

ML: Oh, you did ask me where I teach. Sorry. You asked me a couple times.

JL: Yeah, that's okay. Well, I want to make sure that people know how they can connect with you, so website, social media, email, any of that you want to share?

ML: Sure. As of now, because I just got into where I am, I am producing my online program, but you can find me at www.rootedstrengthmethod.com. I have an IG with the same name, but then my personal IG that's open is morenacapoeiraBJJ, and then I have a YouTube channel as well. I'm trying. Right now, it's me learning how to organize these things to make it happen, because I'm running after … keeping people in the game. That's what I want. Hopefully, we will have a summer launch for the program.

JL: Nice.

ML: I’m hoping for a summer launch.

JL: When that hits, send me the link, and we'll update the show notes with it.

ML: For sure, for sure.

JL: Awesome. This has been great. This has been a lot of fun, and I appreciate your openness, and your willingness to step into all of these different places, again, openly and yet, bring them back together, because for me, it's the combination of these things. It's understanding that they all interrelate. It's the energy, it's the music, it's the training, it's the shedding of past whatever, that makes it all so valuable, and that's why I love martial arts.

ML: Agreed.

JL: Now we're gonna fade out, I'm gonna record an outro in a little while. This is your opportunity to speak, for the last time, but directly to the audience. We've got a bunch of people listening from all different backgrounds all around the world. What do you want to tell them?

ML: Don't be afraid of the struggle. It is difficult, but that's the spot where the most beautiful flowers bloom. That's it for us. That's it, and believe in your power, because you're the only human in the world to be wearing your skin. No one is like you. You are only. You are magical. You are amazing. You don't need to be like anyone else, and that's just perfect, and that's where power is. That's all I got.

JL: There are episodes of this show that just hit me different, for whatever reason. I've spent some time thinking about why this one was one of those, and I'll be honest, I can't articulate it yet, but it's one that, here we are a week after I recorded it, and it's still sitting with me. I suspect for some of you, you're also feeling something similar, that there's something that came out of this episode that really meant something, and for that, I want to thank Morena, because it was her openness, and her willingness to go to these places that we needed to go that led to such a wonderful episode. Thank you. I'm sure we'll connect at some point. We're not that far away from each other.

Listeners, or perhaps viewers, check out everything that we've got going on at whistlekickmartialartsradio.com. From the show notes, to the photos, to the links, if you want to go deeper on this episode, if you want to check out other episodes, that's the place you can go. If you're up for supporting us and the work that we do, you have choices. You might share an episode, or leave a review, or tell a friend, or contribute to our Patreon.

I'd love to visit your school for a seminar. If you're up for having me, just let me know. We'll make it happen. I love doing seminars.

Use the code PODCAST15 to save 15% off a shirt, or gear, or anything else at whistlekick.com. If you've got suggestions for guests or topics or other feedback, I want to hear about it. Email me: Jeremy@whistlekick.com. Whistlekick social media is @whistlekick. That brings us to the end.

Until next time, train hard, smile and have a great day.