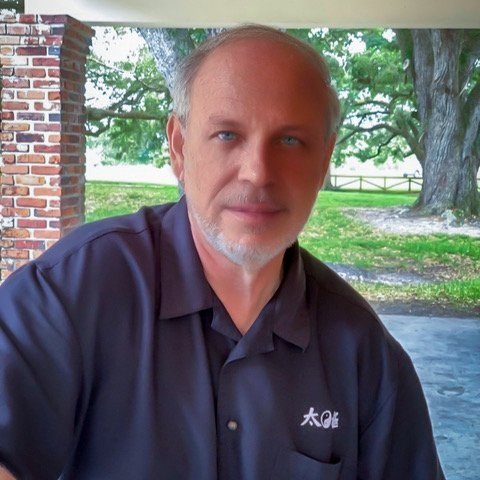

Episode 732 - Professor James Cravens

Professor James Cravens is a martial arts practitioner and instructor at J Cravens Martial Arts in Florida.

I was always interested in trying to find the truth. A lot of people don’t think the truth exists but I wanted to find what the truth was in Martial Arts, and that also carried over to my life and the big questions in life…

Professor James Cravens - Episode 732

Who would’ve thought that there are elements of martial arts in the old western movies? Professor James Cravens saw a lot of those when watching western films when he was 12. Now, at 69, Professor Cravens has found his passion in teaching martial arts and he runs J Cravens Martial Arts in Florida. He trained in numerous disciplines but Chinese Boxing interests him the most.

In this episode, Professor James Cravens talks not only about his journey to the martial arts but the uniqueness of Chinese Boxing and how it was developed.. Listen to learn more!

Show Notes

For more information about Professor James Cravens, you may check these websites:

chineseboxing.com

jcravensmartialarts.com

https://www.facebook.com/CBIISite

https://www.facebook.com/groups/2454578324764945

Show Transcript

You can read the transcript below.

Jeremy Lesniak:

Jeremy Lesniak:

What's happening everybody? Welcome. Thanks for being here. This is whistlekick Martial Arts Radio episode 732 with my guest today. Professor James Craven. I am Jeremy Lesniak. I'm your host here for the show. The founder of whistlekick, where everything that we do is in support of the traditional martial arts and martial artists. If you wanna see all the things that we're working on, our projects, our products, content, you name it. There's a bunch of stuff. Go to whistlekick.com. If you haven't been there in a while, you should probably go back because. It's not the same. It's always changing.

One of the things you're gonna find over there is a changing listing of products in our store.It's how we pay the bills. One of the ways we pay the bills here. And if you use the code PODCAST15, you're gonna save 15%. We've got everything. I think the lowest cost in the store is $5. We've got $5. What we call our swag pack, which is a random selection of stickers and other flat items. We can fit in an envelope that we send off. With a coupon for at least $5 on your next purchase. Some people are spending $5 getting stuff and getting coupons up to a hundred dollars. Some of us go as far as that, but that's a whole other discussion. If you wanna know more, go to whistlekick.com or email me the show. This show whistlekick martial arts radio gets its own website and it is, you probably guessed it.Whistlekickmartialartradio.com two new episodes each and every. We're working hard to connect, educate, and entertain you and the rest of your traditional martial arts brethren around the world.

And if you wanna help the show and the company and the things that we're doing, you've got lots of ways that you can help us out and make sure that we remain here supporting you to make a purchase.You can share an episode or join our Patreon, patreon.com/whistlekick. It's a place where we post exclusive content. And if you contribute as little as $2, you're gonna get access to at least some of it. You wanna know who's coming up on the show. The only way to find out is in the Patreon. And at $2 a month, you can find that out and you can help support us.But if you want the entire list of all the ways you can support us whistlekick.com/family, you gotta type it in.

One of the things that we've heard over the years from our guests is this notion that they search, that they. Maybe they have an idea. Maybe they don't have an idea of what they're looking for, but they know it's out there.And sometimes people find it quickly. Sometimes they find it quite late in life, but today's guest is someone who found what he wanted after a couple tries, but was still quite young and has spent his martial arts career exploring and bettering that not only that, which he found, but him. And if that doesn't make any sense at all, it will. After you listen, here we go. Hey James, welcome to whistlekick Martial Arts radio.

James Craven:

Thank you. It's good to be with you, Jeremy.

Jeremy Lesniak:

I appreciate you coming on. I appreciate your time. You know, look through your stuff that you sent over to us. There are some interesting things. You frame some stuff. Here we have 700 plus episodes. I haven't heard people frame things like this before, so I've got a feeling we're gonna get into some good stuff and I'm looking forward to it. Now we're gonna start in kind of a simple way, the easy way. It's the beginning. It's your origin. When did you get into martial arts?

James Craven:

I was 12 years old and I'm 69 now. So it's been a journey, but at 12 I was, I guess what always interested me were some of the old shows in the sixties that I used to watch. So I saw The man from U.N.C.L.E. I like that and the Wild Wild West, and I'm probably dating myself for a lot of your listeners. , James West was an actor and. It was a Western setting, but he would fight differently. He would use a hammer fist to the kidney and things that were just a little different than the normal westerns. So, I was always curious about that, but anyway, on my first day, walking home from junior high school, a guy threatened me with a knife. He never did end up doing anything. But I had a conversation with my father later that day and he said, well, you gotta learn to defend yourself.

So I began looking for someplace to learn, found an individual at the college where my parents taught and the individual taught me a few times that summer. Or rather that fall. And after that he disappeared. And so there was a class that started at the temple university in Chattanooga, Tennessee, that's where I began really a little bit more study. The beginning I had a teacher who had a background in karate mostly and so I studied with him. He did basics, but mostly what he did was he kind of got to the form, got to the fighting pretty quick, the sparring back then. And so this was sort of a sparring school. And so for two or three years, there were a couple different teachers that came in one from Shorin-ryu karate. They were also fighters. And so, we did some basics. We did some forms, but primarily we were a school that traveled on weekends to do tournaments.

So the tournaments back then were, I won't say realistic, like, some of the fighting. Today is, or like the mixed martial art pretends to be. But it was interesting because there's no equipment. In fact, some tournaments wouldn't let you wear a padding on your wrist or your shin or anything. And the fighting kind of followed a pattern, at least the tournament circuit that I was on. And what it was is he had a rule session at the beginning of a tournament and it, in general, they said, , it's a light contact tournament. And, , so for below black belt or below brown and black, , you can hit lightly to the body.

You can't hit them in the face. Come close to the face, but you can't hit the face for the brown in black belts, you can hit hard to the body light to the face, and that was about it. But almost every tournament, as each level was sparring, it would accelerate. And, you had some people against it, but the tournaments we were in, mostly, ended up just being real strong contact, for everybody even the lower ranks. And you realized after a little while that the other person was really trying to hurt you . So in that sense, there was some realism in that you knew somebody's gonna try to knock your head off there wasn't realism. And of course the target areas and ground fighting and all that sort of thing. But, they were pretty rough tournaments and nobody. Is wearing mouth pieces at the time for any protection. And so it was an interesting time and there are, of course, hundreds of stories I can relate to you, I guess in back…

Jeremy Lesniak:

I’m doing the math, you were young. You're young during these competitions.

James Craven:

Yeah, I was in the beginning when I was 13 years old and I was in the White Yellow Division and within two or three years, I was in the Green division.

Jeremy Lesniak:

And then what did your parents think about that? You go to your father, look and the trust of it is let's protect you. And then you're stepping into these competitions.

James Craven:

Yeah, and it actually, the self defense part kind of faded away fairly soon. And at the time there was pretty, pretty much excitement on the sparring. It was kind of scary for me then, buddy, it was as far as their response to it. They liked it. Of course my mother would never come and see me compete. She was scared to death of what might happen to me, but sure. My dad liked it. And so I had no problems there. Anyway, after that I got into an organization called [00:09:02-00:09:04] association. It was run by a man named Daniel [00:09:07-00:09:08]. In old times, he probably would've been known by most people in the martial arts. Tournament world, at least, although he wasn't that big of a tournament guy, but he did go to them. Anyway, I say that back then there were like, a lot of Kings and Kingdoms.

So the kingdoms were Martial Art Societies. That's run by somebody who's the king and everybody pretty much is servants and that sort of thing. Well, this was kinda one of those, although this man was always nice to me and I had to travel up to Connecticut to study with him in the summers as I was in high school and, and then , college, but he was.traveling a lot himself. So I'd meet him at a lot of tournaments as I was studying with him. And, the association had a lot of nice people in it. So I met a lot of good people there.

Jeremy Lesniak:

What was it about him or his association or his, that you were that kind of a kid from Tennessee to Connecticut? That's not a small thing. That's not down the street. That's a commitment.

James Craven:

Yeah, well, I was somewhat naive, but I was convinced that this was the greatest teacher in the world and the greatest art in the world and got it. So I was somewhat, you know, overshadowed by those young naive things. So, but as soon as I could drive, they let me go up for, you know, periods of weeks in the summertime. And so it was very exciting and I was heavily into martial arts. I played sports. A lot as a youth in junior high. And then I had an injury that cut my heel pretty good on the back of the spokes of a bicycle. I was okay in junior high school, but then in high school, the workouts got harder. The running got harder and the back of the heel would never stay healed. It would always have skin grafts on it and everything.

But it would always bleed. And so, when I started Karate, of course they were barefooted and I didn't have anything rubbing it. So I was okay. And then they came out , you know, after the converse shoes, they started coming out with these very comfortable athletic shoes. And so I could wear those and not have a whole lot of problems. And then I got into these Chinese arts with the association and they wore shoes. So , I didn't really do a whole lot barefoot except those first three or four years. And it protected my foot somewhat. And she was comfortable. So anyway, this association, they had a lot more forms and other things that they did a lot of shows they put on.

Lot of stunts they would do, but the sparring was still heavy and still, I continued pretty much in that vein for, it lasted up to the first 10 years of my martial arts history. And so, it kind of culminated with a trip to China that the teacher took us on. It was a six week trip to Taiwan actually. And that was in 1970. and it was a very memorable trip, lots of interesting things. Somehow my teacher got the University of Connecticut to sponsor it and we were somehow connected. We were connected with the Guoshu Federation Republic of China, which is sort of a martial art.

Area of the government in Taiwan and it was a part of the ministry of education. So we were hosted great. They took us to some wonderful meals and got introduced to Chinese culture quite a bit. And then they brought, oh, it was about four or five demonstrations. So we participated in some of them. But what I didn't realize is some of the people I saw in the demonstrations were some of the people that my teacher. What I have is teachers a little later, my teacher that came after this association.

Jeremy Lesniak:

Oh cool.

James Craven:

But anyway, yeah, it was cool. But the organization, without being real negative, there were things in it that would bother me ethically. And I knew it was somewhere I should leave, but as the young person and not knowing where I would go. That kind of thing held me there probably a lot longer than I should have stayed with that organization. But I had made the decision and some things happened on the trip, not to me personally, but some, some of my students that convinced me that I was going to leave and I had one guy in mind that I was going to study with who I'd met. Very strange eccentric character. His name was Christopher Casey. And he was like an eccentric genius type guy who was not really impressive as an athlete, but was really smart. And he was in love with martial arts and philosophy. So when he was in, College. He graduated with a degree in philosophy he wanted to go on, but he loved the Eastern philosophy mixed in with the Western philosophy.

And at that time, universities would not, were not acceptable to doing, thesis or dissertations with any kind of promotion of Eastern philosophy. Cuz they, the academia actually looked down on it. So he decided, okay, I love martial arts. I'll just go into the insurance business. Get up to mid-level and travel all I can to study martial arts with teachers I can get. That would've worked out fine, except he said everyone he worked for was an idiot. So he kept moving up the ladder and he would, he was vice president of a couple companies and didn't like his work, but he was just able to do a lot very efficiently in a short period of time.

And, finally he decided to go into reinsurance and that's kind of international. A little bigger stakes situation. He went to see Seattle to learn the craft, and then he got hired by a German company in Hanover to set up a sort of Lords of London division of that insurance company, because at the time Lords of London was the only one that did that stuff in. And so Germany was wanting to compete with some, so he set them up and then they sent him back to the US to set up a subsidiary of the company. And those were the best years when he came back, that I had everything up to then I had to chase him to different cities, cuz he was always getting a new job.

Jeremy Lesniak:

And you were just following him around. The focus was the training and you'd kind of carve out what you were doing for money and living situation wherever you were.

James Craven:

Well, yeah, he would come back to the Atlanta area. Okay. And that's where his home was originally where he grew up. And so when he would make his trips back, I'd meet him at motels for a weekend. And then when I could I'd fly out to wherever he was. So it was sporadic, but it was good.

Jeremy Lesniak:

And so lemme jump in and let me, let me ask you a question because you've talked about some wonderful people that you've trained. And it sounds like you had enough context by this point to know what was average, what was poor? What was exceptional? It strikes me that at the time, at least at the time you would've thought of this man as an exceptional instructor, what was it about him and what he was teaching that you thought? I need to go chase him around.

James Craven:

Well, Mr. Casey. Like I say, he was an unusual person. And so, actually it was really strange because my former teacher, he knew this guy and that's another long story, but he knew him and he said, you know, one thing about the pile is you had whatever he taught. And then anybody that came into the organization brought what they taught. And so it was a big mixture of things. Sure. So he knew this guy and said, this guy's very knowledgeable. You ought to study with him. Well, he was in Atlanta. I was in Chattanooga. So it was about a two hour trip. And so I began attending. He was teaching at Georgia tech and I began attending a class and he taught primarily Chinese Kempo and some Shaolin at the time.

So I learned a lot of Kempo at that time. And so then when I became his official student, when I left, he's the one I wanted to go to. Even at that time, I knew that he was doing his Kempo, he was pretty rough and brutal, but I never thought I could whip him, but he knew a lot. And I wanted to study with him because he knew a lot. And so that's why I chased him around. But , when I had my first private lesson with him coming back from China, it was an interesting lesson. Maybe I'll tell you a little bit about it.

Jeremy Lesniak:

It sounds like a story we wanna hear. Yeah, well, there's a little bit of a smirk on your face that suggests there's something there.

James Craven:

Yeah. He was really good in Chin Na. And so I was really weak in my Chin Na. And so that was one of the motivations to go to him. And so, I'm thinking he's gonna start teaching me Chin Na or something. And so he said, well, let's spar. And I'm thinking, oh no, you know, I'm gonna embarrass this guy. He's not gonna want to teach me how I can stay away from him and try not to hurt him? Cause he wasn't real athletic looking, you know, so anyway, we began to spar and, and he would, you know, judge his distance well and everything. And he would kind of corner me cuz we were in a basement. So I couldn't run away from him forever. So he would go in and get me once he touched me, he was in control of me really well, and then he would take me down.

So the first time he did it, he took me down, tied me up on the ground where I really couldn't move. He usually had a hand free where he could've beat me to death while I was in that position. And it was weird cuz he would just sit. You know, and I'd kinda look back to see what he was doing. I couldn't quite see him, you know, finally he'd let me. The first time he said, well, have you had enough? I said, no, cuz I was a little irritated and wanted to have another chance. I said, okay, I gotta try a little harder. Yeah. So anyway, long story short, probably 10 or 12 times in a row. Same thing basically happened. And he said again, at one point, have you had enough? I said, yeah. He said, well, what do you think? I said, well, to be honest with you, I didn't think you could fight. So I am excited that you can whip me and so he then asked me, he says, well, you know, I saw you spar at a tournament.

A while back. And I noticed that in the tournament, you were pretty good at getting your reverse punch and hitting people with reverse punch. And he said, why didn't you ever try that on me? I said I was trying, but I couldn't do anything. You know? And then I said to him, let me ask you a question. Why when I was down on the ground, why did you keep me down? Because why don't we just get up and continue, you know?

And he said, well, if you're gonna study with me, you're gonna study realistic martial arts. He said, you got this idea that you can just go out and spar and punch and kick with people. And then everything's okay. He said, every time I took you down, I could have finished you easily because you couldn't move. And I had loose limbs. I could hit you with, and it says you only get one mistake in a real fight and you may be dead. So he said, you have no idea what realistic fighting is. You certainly don't fight. Like it. And he was right. And it was, even though I consider myself pretty serious for someone my age and studied the issues of life and the questions of life, it hit me that I said, well, you know, I that's just it, I gotta decide what I wanna do in martial arts. Is it a sport? Or is it, you know, what is it? And so that was a very convincing lesson, that there was something interesting to learn.

So that kind of began my path of what we generically called Chinese boxing or energy boxing. And that was the path I took and stayed with him until his death. About 10 years later. And, he was in reinsurance, he got some contracts that he got to be in Taiwan a lot. So he developed some teachers there. His Wing Chun teacher was his one that he, by shifu with [00:23:01-00:23:07]. Taiwan to teach. And also he kind of hoped to move there because even though he was in Hong Kong, after he had the.[00:23:17-00:23:18] province and so forth. It wasn't the tradition that he was used to and Taiwan supposedly was. And so he wanted to go there, but he was never able to get there, but he was a Wing Chun teacher. And then he had a Tai Chi teacher. [00:23:31-00:23:35] He got to study with and he's pretty well known as a master who lived there.

And he had a few other teachers, but his two main ones were the Tai Chi and the wing chun teacher. So anyway, during all this time, he also studied realistic fighting. So a lot of these traditional arts, you're not gonna get much realistic fighting training from them. Some will hint at it. Some might show some things that are realistic, but generally you're using very traditional ways of learning in those arts, but his interest was always the real stuff. And so, no rules and all that sort of thing, life and death encounter. What are you gonna do? So he developed a synthesis, which was pretty awesome. And it was based on high probability, high percentage. You don't choose things like you would in a term and I'll try this today, you know? No, you choose things that through your practice, you are a high percentage at executing. And then you also had a theory in Chinese boxing.

So sometimes he would divide martial arts into two categories. You have those that basically hit and run. And if they're fast, they hit and run. But when they get old and they get slow, they start losing because their art is based primarily on their speed or their combined power. He said the other art is one that picks the right time and goes in to finish. And that's what wrestlers would do. Of course, they're in a sport. And a lot of the Jiu jitsu people in MMA do that. And people in MMA do that, but he was doing that back then. And he had studied a lot of jiu jitsu too, but he still preferred the more realistic.

In other words, if you take a guy down his buddies over here about to kick you in the head or step on your hands, he was wanting ways that could finish and go down at the last resort if he had to. So, he just referred to it, he had a lot of names for it, but Chinese boxing is what we've called it through the years. And it was a realistic study. He broke down the encounter into an offense yield encounter, and stopped hit entry, and then touchpoint and with touch. A lot of the people he studied demanded this type of dealing. Within touch like wings, Tai Chi, push hands, joint hands. So he required that touchpoint. And then in touchpoint. Once an advantage is achieved, then there's a forward pressure to get the finish.

And so the finish was the last study, but the forward pressure was the connector and the connector between entry and touch was something we 've heard called critical distance And that's the whole idea of the start is you have to get an advantage, especially if you're the weaker fighter. You're not as good or strong, you have to have. A speed advantage or not a speed, but a jump start somewhere within the encounter so that you have a chance to execute this theory. So it was a challenge because I couldn't look and see anybody else doing it that much. And so, um, I had gotten a lot of sparring experience. So I'd learned some of the things you learned from that as far as timing and that sort of thing.

But, this was a different method I wasn't used to going in and trying to finish. I was weak inside when I went to him, that's why I wanted chin and I wanted, you know, other things. I'd done a little bit of boxing, but not much. so I was weak inside. I wanted to get stronger inside and his key thing, he had tremendous projection, even though he wasn't as athletic as I was, he had great touch. So in touch. I couldn't get advantage on him. I was usually disadvantaged. And then when he would seize you, he had tremendous projection in his hands to get to the finish that he wanted.

Jeremy Lesniak:

Can you talk about that touch point? I feel like I understand it, but if I only think I understand, I'm sure we have some people who definitely don't understand. So if you could unpack that a bit for us.

James Craven:

Well, you know, again, every teacher is different, so I hate it. Paint a broad brush on it, but, for example, [00:28:07-00:28:09] is primarily done in touch with each other. And while there may be times that they want someone to be aggressive and move forward while they're doing south, it's sticking, but it's not forward pressure as we say it. As we think of it. So you learn to be balanced and touch. The problem is in a real fight. It's not gonna be so controlled in, in a spot. It's usually gonna be in motion. And so a lot of the touch, you know, someone pushes here and I go around or whatever, a lot of the touch that you learn is while you're standing here and there's no pressure and when there's pressure, there's more impact or more resistance. And when there's more resistance, your touch is not the same as when you're sitting there without the resistance. It's a different touch. And it's a whole body touch.

So his goal was to get in advantage so he could apply the forward pressure, which was backed up by. Rooting from the internal arts heavy rooting, not the kind where you stick your feet in the sand, try to stay there. This is the kind, while you're in mobility in motion, how do you stay down while you're in motion? And once he'd get an advantage and then that pressure from his root, he could. And once he turned you, he had seized you. And he had a lot of great finishes, you know, to finish. So out that way, push hands were that way.

And now when I first got into push hands, it was quite a lot sort of like wild, wild west. It wasn't very sophisticated or what traditional push hands were. So we just, we played and we did a lot of things that weren't in push hands and didn't realize what push hands was for. But push hands is just a, you know, usually a little further away than Chi. Except some chin style is very, very close, but, but most of it's a little bit further away. So you're developing a touch at a little more distance and then joint hands from UA. You're touching at the wrist, you're walking a circle and then somebody attacks and you go from there, you learn, you know, things to do. But, , and this is a little bit further, but still in touch so you learn a sort of a scientific process on entry. For example, you don't enter. Like so many people just attack outside of critical. Well, if they're the best aggressor and they're the best martial art there, and they're the fastest, they can go in and accomplish what they want to.

But as they're more equal with their opponent, when you attack outside of critical, you certainly make yourself vulnerable against somebody that knows how to stop hit, or is a good yielding counter fighter. And doesn't not afraid of you that kind of. So there was an art form to attacking at the right distance and to attack offensively. You're gonna have to have deception. You're gonna have to have, , pre shuffle a, , um, broken rhythm type. Entry so that you have a surprised entry, you have to be non telegraphs. So they don't see where it's coming from. These are a lot of skills. So offense is the hardest thing in the sense that you gotta have more skills to get this takeoff or this quick entry, the yield encounter fails a lot because the aggressor gets in too close and the guy yields, but he can't counter cuz he gets just, just over overblown. Brucely said, , yield encounter is. Theory, but it doesn't work too much is what, what he, how he described it. And so, , but there's, if you control your distance prior to it, then yield encounter can be excellent and then stop it. Probably the Supreme technique, a little scary to do, cuz you're moving toward the attack.But if you see Telegraph, then you can move and intercept that attack with some practice and you see that very little, even in the MMA, you don't see it much. I, I remember studying MMA fighters and, and you see it once in a. And you see it often by good fighters when they do it, but they're, they usually back up, you know, and the aggressor just catches 'em and that sort of thing, or that's just what you see a lot of.

Jeremy Lesniak:

So it's a pretty strong instinct when you're confronted with violence or a threat to remove yourself, you know, you're, you're have to overcome that and not everybody puts in the time to work through that response.

James Craven:

Right. And that's a big problem with Chinese boxing is how you do it. Practice realistic finding and stay safe. Because you say, okay, let's go out and do Chinese boxing. You're all right. Somebody's gonna get hurt. No matter how bad we are, you know, eventually somebody's gonna get hurt. Probably both. So, how do we practice? So, it's a challenge, but there's ways to approach it. And you usually have to work on something while you're compromising, giving courtesy to something else but there's ways to do it.

But that's the biggest challenge. And it's not according to rules. So, it's not the ideal thing, but it can be accomplished through lots of exercises and drills that takes a somewhat creative mind. Casey had a very creative mind, And he left us with that challenge when he left. So anyway, that that's, kind of the picture of what was happening with Mr. Casey and Chinese boxing. He started a Chinese boxing Institute international in 1981. He made me the president of it. And after he died, I've kept going under that all this time. And I don't wanna say purpose. That sounds dismissive of the focus of that organization. Yeah, well, it's really small. Okay and when he had it, he had all his teachers in Taiwan that were board members. And when I had it, I just kept the name, but I didn't really connect with all the board members. Although I connected with one of his teachers for a number of years. And, we also had a German component that was going on, a branch of Chinese boxing there as well.

I was traveling at the time in about 20 states and traveling about every other weekend of the year to teach. So I had schools and different groups that were following it. And as I got older, I started. Traveling less, teaching more locally. I still go back to my home state, Tennessee. I'm in Florida. I go back to Tennessee every three months and teach groups there. So we have a small group, but we have people that have been in love with this start for a long time. And so, even recently we tried to start. A new endeavor to bring more youth into the cause we are looking around one day and say, most of our best people are in their sixties, you know? This isn't gonna last. We gotta get younger. We had a few younger and we still do so anyway, we started something. We called the Chinese boxing instructors association and we meet usually three times a year for camps.

I've put a very large archive of videos for the curriculum online so we have a membership and we try to attract the guy that's helped me who is really good at helping people in this sort of thing. And he lets us use his school, which is really nice up in Woodstock, Georgia for our camps. So anyway, this is trouble if we started it right as COVID hits some martial arts schools were going under. And so it was hard to track because his goal was to attract established schools when they want to have a new program in their school. And so that was more of what he's tried to do. So anyway, we're still plugging in and that's something though that we did recently, but after those years I moved to Florida after his death and started working full time at martial arts pretty much from 1988.

And but then, I had done Tai Chi with Mr. Casey,[00:36:49-00:36:51] was my main art at the time. But after I moved to Florida, he had always encouraged me to look for a Chen Tai Chi guy, because he said, they're fairly Marshall. And , as far as internal skills, that might be something he'd be interested in. So a guy walked in my school one day and, so I started Chen Tai Chi, and then I went on to study and have been with him since about 2000. And he's probably one of the most famous Tai Chi teachers. And so I learned a lot from the internal art already. Casey had instilled what we call 10 principles into the art. The principles don't help you. They don't guarantee any kind of success, but what they do is they enhance. In other words, we say that a real fight is when everything, the winner of a fight is because of certain reasons and all these reasons, size, speed, timing, toughness, all these things come together to determine who wins that fight, theory and martial art. But you know, all the smarts in the world aren't gonna handle someone too fast who knows what they're doing.

So, we realized the place of each thing. And so the principles are usually pushed in most of the internal arts with the dualling that we mentioned, the, the touch. and also they teach you to root, , depending on the teacher, how to do that, but they teach you to root, which is an essential in Chinese boxing basically, because root is bottom heaviness.

So if you're up upper bodies loose and you're very strong below, then rod is there's connection with somebody. If they're not rooted, then in general, let's say you're the same. You'll have an undertow effect on them on contact. And if you can continue that attack they're not in the best position to defend it. So it became important and it's something I never saw anybody doing in martial arts. For the most part. Some people just say root means you're low, but it's not low. It's a body state that has to be developed and it wasn't easy to develop. It. Wasn't something I would've ever been attracted to. But I understood that he was controlling me. My teacher Casey was controlling me for some reason. And that was one of the things he could do. So, rooting became important. And you learned that in the internal arts, as they teach you how to relax and to sit. Sit over your skeleton, the strongest possible position and all these sorts of things. And you had principles like it's called the six, nine changeability principle. This is whatever you do in Chinese boxing.

You, you do it in a way that you can change. So for example, you see in a lot of fights, you see the guy really going for it. Okay. If he hits his target, he's successful at that moment. If he misses his target and that other guy doesn't run away too far, he's the first guy in trouble. He has a chance, right? So, it means you learn to punch and kick and step and all these things in a way that you can change. A punch that gets deflected turns into something else. Your stepping is at a width. That when the, like, if I'm coming on the opponent, he's trying to block away and I'm just about there. And he suddenly cuts left or right. If my feet are placed, well, if my root is there, I can stay with him and still have a chance. But if I don't discipline how my steps are, then I'll never catch him on that. And it starts all over again with the back to neutral. Hmm. All of these things are terrific principles, unitary principles, learning to hit with your whole body and not just the waste, but also.

Coming up from the ground are doing what we call sludging, which is dropping down and connecting the waste and the synchronization of the whole body to get the most out of a technique. This is taught in internal arts. But a lot of the internal arts don't take it into realistic, fast movement. And so, all these principles would enhance whatever you could do in your speed, in your timing and your strength and all that sort of thing. So the principles became a great focus for us because we knew to get the most out of us. We had to get the principles, you know, working with everything that we did. So then Chinese boxing encounters were the art of fighting and in principle were these enhancements, which made us better in whatever we did. Like I say, you can root all you want to, but that's not gonna win a fight for you.

You know? You know, a process, but the principles became a really important thing to us. So that's the principles were enhanced greatly, but my study with Tai Chi and some people that had been deeper into internal art than Mr. Casey had. So anyway, that's kind of the educational part of my story there

Jeremy Lesniak:

It's interesting how these things are connecting the tangible elements that you're talking about. It's all quite sensible and makes sense where I want to go next, though, is about… you haven't talked a lot about. Right? Like, if we go back from a very, very early point, you wanted more, and I'm sure that even among your peer group, at each point you wanted more than them, you wanted more knowledge, you wanted more success. However you define it. At least that's what I'm taking based on not only your words, but just my understanding of the way people generally operate when they're in a martial arts context. First off, is that a fair statement that you wanted more at each point?

James Craven:

I think I was more motivated than most.

Jeremy Lesniak:

Yeah. Okay. All right. So then the question is. Why, what was it about you or your upbringing or your goals or whatever it might have been that made you more motivated than others?

James Craven:

Well, I loved competition and competition makes me miserable, but I loved competition at the same time. I understand so much. Hated tournaments, you go around the stands and you get feeling sick and you just, and once you're out there, just go ahead and hit me once. And now I relax, you know, that kind of thing. So I hated competition, but it drove me probably during those first 10 years. I'm from a family who had a very spiritually inclined religious background. And they were always throwing the big questions of life at me. And, so I pretty much ignored them most of the time because I was just interested in any kind of sport. And then martial arts was my main thing. And so, I end up getting married pretty early and having kids so that sobers you up and changes things quite a bit too.

But that was my thinking and was getting more serious. And then when Casey sparred with me that day, then I had to really do some thinking. I said, well, I've just been playing all my life, you know, with martial arts. And there's not been any real serious study here. He was a philosopher and he was very serious about life. We did not have the same worldview, but he taught me a lot and I became very serious about realistic martial arts. And it turns out not to be an easy thing to do to really make gains in it. But that's what motivated me because as I got more serious in life, I had to try to answer the big questions of life and come up with a conclusion because everybody's got their religion, whether it's a religion or not, it's their religion. It's what they believe. It's what they have faith and what guides them.

And it's the glasses. They look through the way they see everything in the world. So I was always interested. In trying to find what is true. I know a lot of people don't think the truth exists. I wanted to find what the truth was in martial art, and that also carried over to my life. And you know, the big question of life is there actually a God, because if there is everything changes for there on if there's not everything changes. Like, what you make big decisions on is gonna really determine your directions. And I found that in a martial arts study and I found it in, you know, realistic life study.

So that's, I don't know if that's the why to you, but martial arts did not become my all in all. It's not what I live for. It's not what I think is the most important thing in life, but am I interested and do I continue to be interested and continue to study Chinese boxing and the internal arts? Yes, I do. And it's one advantage, I guess it's cuz it's also been my living for about 30 years. So that's a motivation. Why too, but, I actually have a teacher. That's what I was born to do teach. And you know that when teaching's easy and when you go too long on your lessons, you know, you're a teacher. And I'm doing what. I guess I was built to do and I can teach, I teach stuff to people about the computer and I can teach stuff about martial arts. I love to teach. And, so that I think is overbearing. Why as well, to what makes me go, what makes me tick?

Jeremy Lesniak:

We've had plenty of conversations on this show about faith, religion, spirituality, and we've had plenty of people who have talked about the philosophical elements of their martial arts training in religious context. And we've had plenty of people for whom they are why related to martial arts tracks back to their faith. But you said something that I think might be unique if I'm understanding it. So I'm gonna ask you to clarify if I'm not, it's almost like you've described martial arts as your as a toolkit, which we've said here before many times, but your perspective onto the world, if assuming we all look at the world, it's with some kind of unique to us perspective, you know, I might see blue a little bit differently than you see blue, but we're close enough. We can agree that it's blue sounds like you look at the world through glasses that are Martial arts.

James Craven:

Well, partially, maybe because, okay. It was in the study with Casey that he made me see how distracted I was, how I didn't have a focus, you know, I wasn't focused in well, so he taught me some logic , you know, and in his art was interesting because it could go logical as far as it could go, but he also taught just like in this difference between Western and Eastern philosophy, Eastern philosophy is a little more ambiguous and it's a little less logical and it's a little more feeling and all this sort of thing. So he believed. Both were involved. For example, we have the logic of our encounter and the distances that need to be a certain way for something to allow you to get a head start and all this sort of stuff, which we worked toward. But there's also the touch part. How do you explain touch?

Well, you say I do this a hundred times, so I'll do it sort of, but some people never. A sensitive touch. And sometimes even practice won't get it. And it's because the way you practice is so in situ as well. But anyway, that's another rabbit trail. So I think that because he taught me these things of logic and to think more clearly on things. I think that what I had already been taught, I realized I couldn't defend it. Because, you know how so many people lose their faith because they go to college and the professor makes a fool out of them in the first biology class or whatever philosophy class.

And, but they're not taught, you know, it doesn't matter if they've been churched or not, they weren't taught. So I got this tremendous interest in what we call apologetics. It's a Christian apologetics, which is defense of the faith and the philosophy behind. And the arguments for the existence of God and then how that carries on and continues toward a more specific belief. But the martial arts influenced my worldview because my teacher showed me how, I didn't know how to think. Real well and when he showed me that, then it helped me a lot in the stuff I'd learned in the past to realize, well, is this bunch of garbage or is it possibly true? And so these are the big questions for me. I like the big questions why I do this.

Jeremy Lesniak:

So what about the future? Right? We've talked about the past. Generally on these episodes. Most of what we talk about is the past, because it's what we know it's, what's happened. It's what we can pull from. But I also like to talk about the future, you know, if you're still speaking or you are speaking what seems to be very passionately about teaching. You're going to remain teaching.

I would expect for a time, um, goals with this organization and, and getting younger people involved. So if we were to circle back, you know, in a few years, three years, five years, what. What would you hope we would be talking about? What if I asked you for an update? What would you want to be saying?

James Craven:

Well, I'd love to see that arc, that those of us are great and unique and all this. I love to see younger people get a hold of it and we've got a few, but I don't know if it's enough to last, you know, be in my lifetime or not sure. And so I'd love to, you know, if we circle back, be able to tell you that there was a growth in it. It's kinda, you've done a lot of things. A lot of people want to read philosophy because it's too hard. It's not interesting or whatever to them. And a lot of people don't wanna do Chinese boxing because really there's no rewards in terms of competition, belt ranking and all this sort of stuff. There's a great reward in discovering truth and, and, and fighting and so on. But, I've always. Probably I shouldn't be a leader of this organization. but I always had kind of a realistic view that a lot of people just aren't gonna even go into this. That's gonna be hard. And,and those that do like it, some of them are gonna go on and do the work and some of 'em aren't gonna do the work.

So you got some that will do the work. So I'm just realistic that it's gonna be small. It's gonna stay. But, I would hope that there's more people that are involved. I've been teaching old people since I'm old. I've been teaching old people Tai Chi, in wellness centers, and different places for the last seven years. And, actually it's on a so different level because these people probably you're lucky if you get one in a hundred that practices 30 minutes a week, you know, so, you know, you're not dealing with seriousness of what I deal with on the other side.

Right? But at the same time you're doing something actually positive and it helps their health. And sometimes you get really good feelings that these people are benefiting from this type of stuff, even though it's not the Marshall stuff by any means. So that's sort of a contending feeling. So that's why I keep doing that. Just be a people person, not to be a martial art. Geek to people, but to treat people like people and care for 'em and try to help 'em.

Jeremy Lesniak:

If people wanna get a hold of you, if they wanna learn more about this organization or anything, where would they go?

James Craven:

I have a couple websites. One is chineseboxing.com and then has a personal site that has actually a little more on it. It's called jcravensmartialarts.com. So those are the two websites they can email me at, cbii@mac.com. So that's kind of a short one. And we can take it from there if anybody wants to contact us.

Jeremy Lesniak:

Cool. All right, we'll link the websites in the show notes where people make it easy. This is your shot to kind of close us up. I'll record an intro in an outro later on, but. You know, we've talked about a lot of things today. And how do you wanna leave it with the audience?

James Craven:

I probably haven't spent a moment thinking about that but I appreciate you, allowing me to come on. I'll be honest. I don't think I've done one of these in my whole life.

Jeremy Lesniak:

Oh, wow. You did great.

James Craven:

I never would. I never would be against it, but I mean, I speak to the groups a lot, but, I've never done one of these and I wonder why, but I just, my student, I think, listens to your podcast. And so he asked me if I would be interested in coming on. And so that's when he contacted you, so thanks to him. So kudos to you, Jeremy.

Jeremy Lesniak:

Thank you, James. We've heard from a number of guests over the years about the importance of knowing history. But in this episode, we talked about the importance of passing on information, passing on knowledge, because you can't know history. If that history isn't shared with you. And I hope those of you out there who are maybe a little less prone to tell your students stories. If you're an instructor, tell your own story. Even if you're not an instructor to the people around you, I hope you'll find some inspiration in this episode to do that because it's critical, the better the context we have for where and how, what we trained came from. I think the better we can understand why we do it and how to deepen our relationship with it. So I think professor Cravens for coming on. And for giving us this opportunity to hear his story. Thank you, sir. I appreciate it.

Listeners, if you wanna know more, if you want to go deeper, all that good stuff. The stuff we talked about in this episode, whistlekickMartial radio.com separate page for each and every episode. They're all there. We don't take 'em down. If you're looking to search for something. Oh, there was an episode where they talked about this. That's what the search function is for. You wanna support us in the things that we're working on? Whistlekick.com. That's the starting point.

All the things that we do are available over there from our books to our patreon, paton.com/whistlekick seminar. You want me to come to work with your students, teach a seminar, have some fun, learn some stuff. Everybody wins in that exchange. Don't they reach out. Let me know. We'll make it happen. Don't forget the code PODCAST15 at whistlekick.com. Don't forget our social media is @whistlekick and don't forget my email, Jeremywhistlekick.com. I love to hear from folks and that's it until next time, train hard, smile and have a great day.